Refugees are in normal times a vulnerable group facing many challenges, such as poor health, less access to work, and other sources of income. For this reason, refugees in the entire Horn of Africa receive monthly a basic quota of food, thought to be just enough to survive. In Uganda, this is still distributed primarily in the form of food, but some people have started to receive a cash equivalent. The cash is either paid in real cash or digitally. The quota per household member has been 31,000 UGX per month. Basically, 1,000 UGX per person per day.

Due to insufficient funding, WFP announced in late 2019 that from April 2020 it would need to reduce the food (and cash equivalent) for all refugees in the Horn of Africa by 30 percent. This means 700 UGX per person per day. As it happened, this reduction coincided exactly with the lock-down in Uganda due to Covid-19. On 30th March the lock-down started and from April, the food distribution reduced. As a result, many are extra worried about refugees and how they will survive in the coming months. Other worries also include that in the coming months it may be a challenge for WFP to continue to buy the food quota within the available budget. Due to COVID-19 supply chains may get disturbed, prices may increase, and food may be confiscated for government distribution schemes to other groups hit by the lock-down.

Nevertheless, there may also be reasons to think that refugees can survive relatively well since they at least have the food distribution in place, they are already on a list for distribution and the authorities responsible for them have experience in delivering food and cash/digital payments. Such distribution will need to be set up from scratch for other population groups who may have lost all their livelihoods due to the lock-down.

Through the financial diaries study (which already commenced in August 2019) Opportunity International, PHB and L-IFT are closely monitoring how the situation for refugees is developing. To assess how the refugees are surviving so far (up to Tuesday 5th May), we asked food security-related questions to 143 refugees in Nakivale and Kiryandongo refugee settlements.

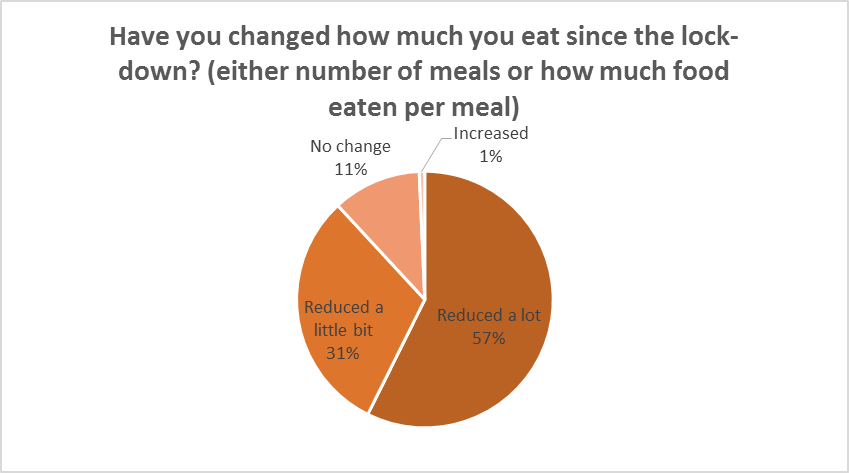

One of the questions asked was whether they have made any changes in how much they eat since the lock-down in either the number of meals or how much food is eaten per meal. More than half of the respondents (57 percent) reduced a lot on how much they ate; 31 percent reduced it a little bit and only 11 percent have not made any changes at all. These changes appear at par with the situation of BRAC’s clients in Uganda.

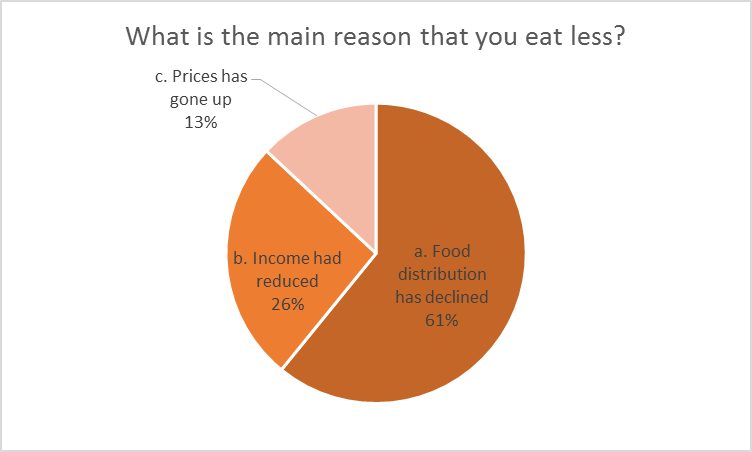

Those refugees who have reduced their food intake were asked the reason. The major reason mentioned was the decline in food distribution. This is followed by a reduction in income and an increase in prices.

We also asked refugees their estimated time that they will be able to buy food and other essentials with the reserves they have, including their savings. About two in five respondents said they do not have reserves at all. Others predicted their reserves to last less than 7 days (28 percent); 7-14 days (16 percent); 15-30 days (15 percent) and only 3 percent said, more than a month.

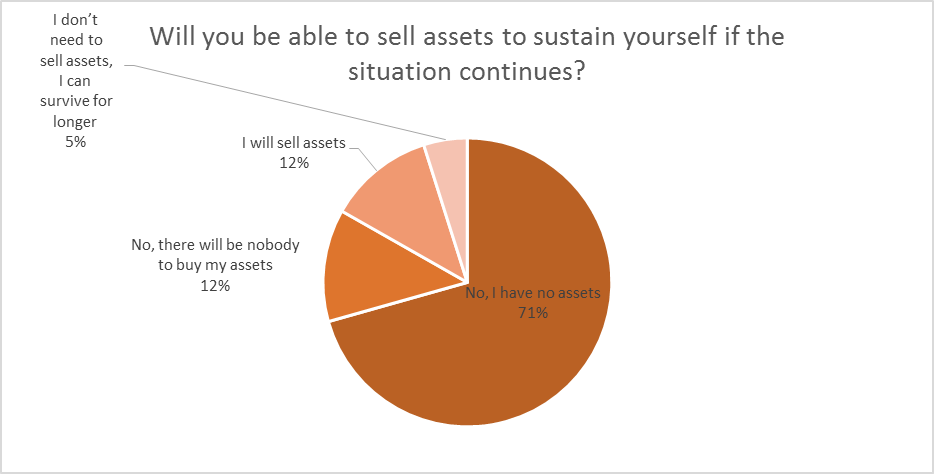

Regarding whether they had assets they would sell if the situation continues, most of the refugees said they had no assets (71 percent). About 12 percent of the refugees raised the concern that there will be nobody to buy their assets. However, a few refugees said that they will sell their assets (10 percent) and a handful of refugees said that they don’t need to sell their assets because they can survive for long (5 percent).

Those refugees who said they had assets to sell mentioned bicycles, computers, cows, ducks, cooking utensils, rabbits, radio, telephone, television, and fridge as their assets.

This article shows that many of the refugees’ survival situation is not ideal, but may be similar to others in Uganda. If the situation continues, it is increasingly likely that they will struggle to put food on the table and otherwise survive. Much will depend on whether May’s food distribution will take place, even if at the 70 percent level of before.

This blog is written using data from the RISE project, funded by Opportunity International, with consulting services from PHB.

PHB collaborates with international development agencies, banks, regulators, and other impact makers around the world to assess, implement and scale digital interventions. We leverage the expertise of our team to support the design of digital finance ecosystems that can strengthen the resilience of communities in need. To learn more about PHB activities, publications and training, visit www.phbdevelopment.com