The story so far

The first blog in this series was written just after an anti-corona virus lock-down was enforced in Bangladesh on 26th March 2020. We showed how the shock was dealt with at the time by the 60 low-income households in central Bangladesh who volunteer as ‘diarists’ in our daily financial diary project. In this new blog, we see what happened in April 2020, the first full month under lock-down.

Money makes the world go round – but in April it almost stopped circulating

Our set of sixty diarist households have all been with us since mid-2017 (the majority since mid-2015). From August 2017 to March 2020, the average amount of money that passed through their combined hands each month (both inflows and outflows of all kinds) was 5.49 million Bangladeshi takas or about $65,000 at market exchange rates. In April 2020, the first full month of the Covid-19 lock-down, it fell to 1.62 million takas ($19,000). If money makes the world go round, the world has slowed down dramatically for our diarists. In this blog, we look at what happened in April in more detail.

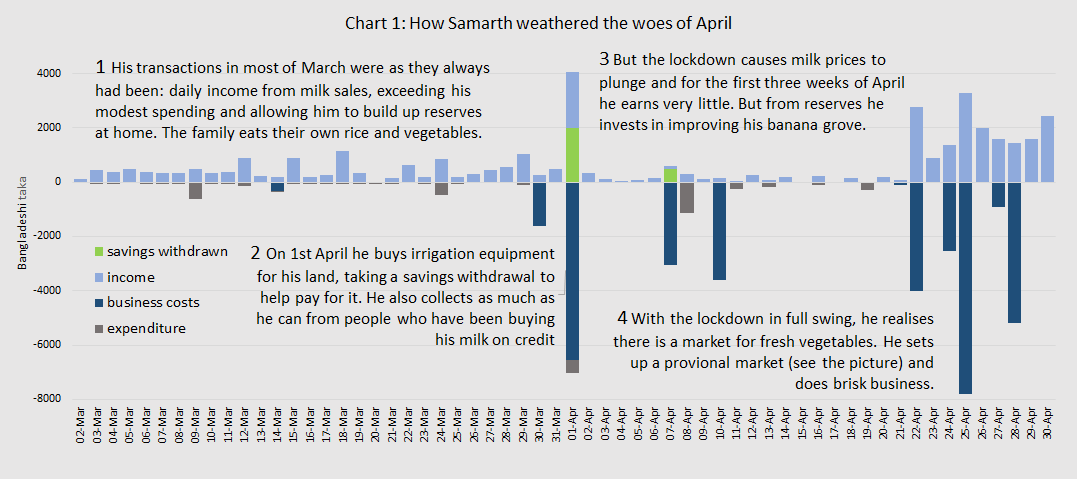

Samarth (not his real name) is one of our most colorful diarists. We have been tracking him since late 2015 but it took us a while to figure out his household economy. He owns a tiny patch of land of about 0.08 of a hectare and share-crops another half hectare or so. From this, he keeps his family of four supplied with rice, lentils, and vegetables. He also loves his cows, which he grazes on common land near his home. By being frugal he has built up some capital and used it in various ventures, including buying a sawmill and lending out money. He likes to smoke ganja (marijuana) and has paid heavy bribes to the local police when they have discovered him indulging in his habit. Our first chart, of his money transactions in March and April this year, shows how he fought back against the Covid-19 lock-down by starting a new business.

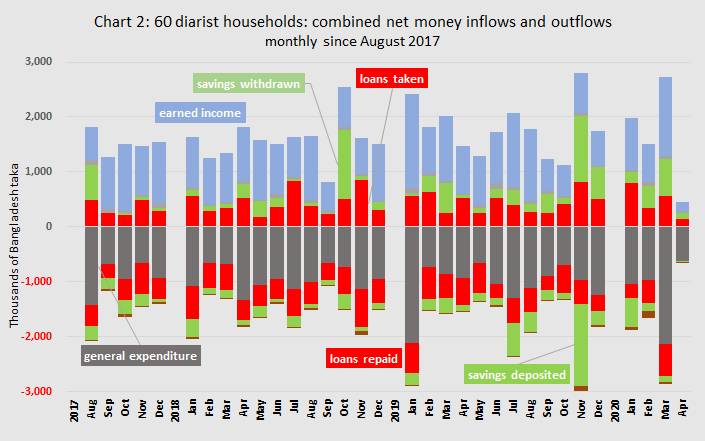

Samarth was able to rev up his transactions despite the lockdown, but this was not true of most of our diarists. Our second chart shows each month’s transactions from August 2017 to April 2020. The more important categories are highlighted – income and expenditure, and the financial flows (savings and loans). To arrive at income we have deducted the costs of doing business (for example buying stock for a shop) from the gross inflows that such businesses enjoy (such as shop sales), so the total values are smaller than the figure mentioned in the introductory paragraph.

Chart 2 shows the scale of what happened in April 2020. Earned income collapsed. But expenditure contracted less than income, pushing most of our diarists into a net cash outflow for the month. Inflows from savings withdrawals and loans also shrank, and almost no fresh savings were made nor loans repaid.

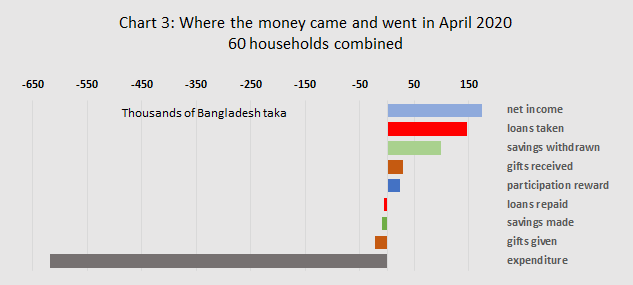

Our third chart narrows the focus to April 2020 and shows totals for the various categories of flow.

Income

Chart 3 shows that despite the lock-down, there was some income. What was it, who earned it, and how did they earn it while others couldn’t?

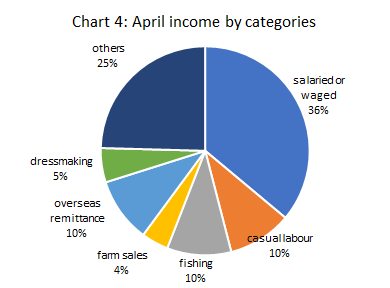

The handful of diarists who get regular salaries or wages – just seven of them – got their March wages in April and accounted for more than a third of all income earned. One has a government job (and so does his wife) and the couple earned 11% of all the income we recorded in the month. But their government jobs are in a public hospital and they are the only diarists to have fallen ill with the virus so far. They are recovering.

It is harvest time, and though the police are chasing people off the streets, one diarist household managed to get two of its menfolk to the fields, and they accounted for another 10% of all income earned. Two households continued their river fishing, sold the fish locally, and earned a further 10%.

So between them, 11 diarist households earned more than half of all the income, while 20 of our diarists – a third of them – earned nothing at all. Indeed, some diarists who run shops experienced negative income in April, having bought more stock than they managed to sell.

Overseas remittances, usually a reliable source of some of the best incomes among our diarists, proved disappointing, as many of the overseas earners lost their jobs or were unable to work.

Expenditure

In April 2020 our diarist households spent four times as much as they earned.

Part of the reason is that a third of all recorded expenditure in April was made by just one of the sixty households – the couple with government jobs in the hospital. Just before the pandemic broke, they had taken a bank loan secured against their salaries and had begun to build a new home, spending freely on building parts and materials.

Chart 5 ignores the spending done by that couple and shows the breakdown of the remaining expenditure. Ever since we began the diaries the proportion of non-construction expenditure that went for food has been around 34%. In April 2020 it more than doubled to 72%. Diarists reacted to the lockdown by restricting their spending on all but essential items. Almost nothing was spent on clothes.

But they still spent more than they earned, so where did the money come from? As Chart 3 shows, some came from loans and savings, and we look at that in the next section. But most came from cash reserves that they held at home. These cash reserves have been depleted through April but are not yet completely exhausted, and although some households are cutting back on food or even missing meals, none is yet entirely without food. Some food relief has become available: from the government but more from private sources, above all neighbors and the wealthier neighbors that local people call the ‘elite’.

Savings and Loans

Our diarists keep a surprising volume of cash reserves at home, but to the extent that they have formal savings deposits – which is also considerable –, they are held in the country’s famous MFIs. When we last checked, in late 2019, 38 of our 60 diarists had savings in MFIs holding between them just over two million takas (about $22,000). The MFIs, however, have closed down since the lock-down started, so none of the savings withdrawals we recorded in April came from that source. They came instead from local co-operatives or from informal savings clubs.

One might have expected diarists to have been distressed at not being able to get hold of their MFI savings, but so far few have complained. We interviewed some diarists about this, and a typical response was:

This is Ramadan (the Holy Muslim fasting month). We expect to get our savings in time for Eid (the big festival that comes at the end of Ramadan). If that doesn’t happen we will be really angry. Meanwhile we are doing our best to keep going until then.

No loans have been made by MFIs, traditionally the biggest source. The loans we recorded in April, which amount to 148,000 takas ($1,741) have all been taken – interest-free – from relatives or neighbors. Not all of them are ‘survival loans’. The biggest, for 100,000 takas, has been a long time in preparation and is a loan by a wealthier neighbor to a very poor household to help them rebuild their dilapidated home. The lender is using her own money to make this loan but maintains the fiction that it is sourced from an MFI loan that she supposedly took, so as to put a little pressure on the borrower to repay in the weekly regular installments that MFIs insist on.

The cruelest month?

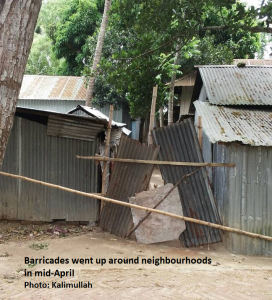

It is too soon to say whether April will prove to be the cruelest month. It is certainly the hardest our diarists have dealt with since we began tracking them. Our diarists are poor – a quarter of them qualify as extremely poor using World Bank income criteria – but by using common-sense practices like restraining all but essential spending, and by calling on the household cash reserves they are in the habit of holding, they have survived the month. Community self-help has been held up, with neighbor-to-neighbor gifts of food and the provision of interest-free loans. Though neighborhoods have put up barriers around themselves to stop outsiders from bringing the disease into their homes, there has been no violence (whereas in Dhaka newspapers report an increase in petty crime as hungry people grab for food). A few diarists, like Samarth, have even developed new ways to make a living. And of the 241 people in our 60 households, so far only two have been confirmed as having the infection, and they are recovering.

It may be that the coming months will prove crueler, as cash reserves run out, or if the lock-down is extended yet again (as of now it is due to end on 16th May), or if the MFIs fail to reopen in time for Eid, or if the disease takes a turn for the worse. We will be watching, and we will report again.

Stuart Rutherford

May 6th, 2020

All fieldwork for the Hrishipara Daily Diaries Project is now being funded by L-IFT. We gratefully acknowledge their invaluable support.

Read more analysis based on the Hrishipara Diaries:

- – Low-income households in Bangladesh give as well as take loans

- – Education and Occupations

- – How are Digital Financial Services used by poor people in Bangladesh?

- – What do the poor spend on health care?

- – How do the poor borrow?

- – What do poor households spend their money on?

- – Tracking the savings of poor households

- – When poor households spend big

- – When poor households spend big part 2

- – Poverty measurement using data from the Hrishipara daily financial diaries

- – Receiving Gifts in Low-Income Households

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.

This first appeared on the Global Development Institute blog http://blog.gdi.manchester.ac.