Last year I was part of a team that conducted a Financial Diaries study of young people in Morocco, Nigeria, and Senegal as part of comprehensive research on “Young People in Africa” that was conducted on behalf of the Scale2Save Programme— a partnership between the World Savings and Retail Banking Institute and the Mastercard Foundation. The team has produced a detailed report on our findings, but we also wanted to share some of what we learned in a more accessible format, and explore the implications in light of COVID-19. This is the second of three NextBillion articles coming out of that study. The first article can be read here.

It makes sense to assume that income is correlated with savings: In weeks when you earn money, you are more likely to save –and the more you earn the more you are likely to save. We asked 117 young people living in the market town of Uromi and in Benin City in Nigeria to keep a record of their savings in “saving diaries.” We then collected data from those saving diaries and interviewed the young people once every week over a three-month period. The data we gathered confirmed this assumption. But young people participating in the study also received financial support from family members and, of course, spent money. The diaries data give us the opportunity to unpack the relationship between income, spending, support, and saving, to see what young people did with the money they earned and the money they were given. Did they only save when they earned money, or did they also save some of the support money they were given? How did the source of money, earnings, or support affect their spending? And how might a financial service provider use this information to inform how they serve young people?

The findings from this research also help us understand what may be going on during the COVID-19 crisis. This data can also help financial service providers anticipate how young people will need to use their accounts, and determine what other services they may need.

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN INCOME, FINANCIAL SUPPORT, AND SAVING

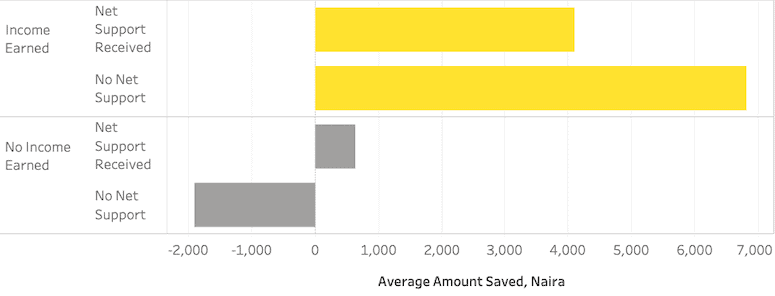

Let’s look at the relationship between saving on the one hand, and both earned income and support received on the other. We need to look at these together because we know from the first article in this series that young people received less support from others in weeks when they earned money. The graph below shows how much young people saved during weeks when they earned money (the yellow bars), compared to weeks when they did not earn (the grey bars). But we split these weeks out between those when they received support from someone else (the top yellow bar and the top grey bar), and those when they did not (the bottom bars). What we see is that when young people in Nigeria earned money, they saved—both yellow bars are longer than both grey bars. (Note: The relationships among variables described in this article have all been tested using various statistical techniques – including correlation and linear regression controlling for respondent characteristics – to ensure that the differences across various types of transactions are statistically valid.)

Due to COVID-19 and the resulting lockdown – and even now, when Nigeria has partially opened up – we can safely assume that most young people are now, in most weeks, in the bottom bar: neither earning nor receiving support. This situation is likely to continue for weeks on end, since many young people have structurally lost all livelihood options, even after lockdown, and their parents have quite likely lost substantial parts of their livelihoods too. In normal times, income, savings, and support patterns fluctuate from week to week, as different members of the family may have earnings during a given week, while others do not. This makes it much easier for young people to manage normal hard times– either excess earnings from others will flow to them, or excess income from surplus weeks can flow to a shortfall week. Now, they face persistent shortfalls – and other family members are all simultaneously hit.

We also see that in weeks when young people did not earn income and received no support, they dipped into their savings—they had “negative” savings, which means they took money from their savings. In those no-income weeks when they did receive support, they put a little aside for savings – but only one-tenth of what they put aside when they did earn income. Finally, we see that young adults (25-30 years old) saved less in weeks when they earned money and received support. This seems paradoxical, but it is not. If they could have saved, they would not have received support. Likely, they received the support because their obligations for expenditures had peaked and their income fell short to meet their obligations.

THE IMPACT OF INCOME AND FINANCIAL SUPPORT ON SPENDING

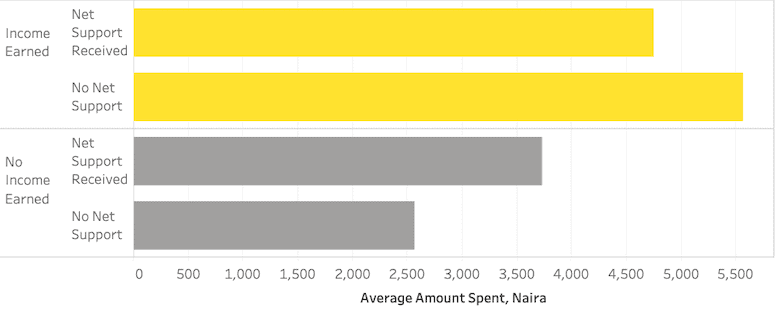

Turning now to spending, we see that young people spent more when they earned income—the yellow bars are longer than the grey bars. They also spent more when they received support in weeks when they did not earn income—the top grey bar is longer than the lower grey bar. Finally, consistent with the savings pattern, they spent more when they earned income and did not receive support—the bottom yellow bar is longer than the top yellow bar—because they were less likely to receive support in weeks when they earned more money.

One of the takeaways from these complex interactions among earning, support, saving and spending is that there is no relationship between spending and saving—young people do not save by spending less, they save by earning more. What this means for financial service providers looking to capture young people’s savings is that they should focus on capturing those savings at times when young people are earning—to use the language of behavioral economics, they need a “just in time” savings product that captures savings right at the time when young people have cash in their pockets. Some of this can be done through marketing and messaging that focuses on getting young people to put money aside in weeks when they earn income. This needs to be married to a service delivery system that makes access to a savings account easy and convenient for young people to use “just in time.” It also might require real-time data-tracking that predicts when a young person may have cash in their pocket to save.

The COVID-19 pandemic will make it more likely that young people will only save when they start earning again because any discretionary spending they might have had—which they may have been able to cut back on to save—will have been taken away by the economic consequences of the pandemic. At the same time, the saving will become more important to young people and their families, as a way to help them weather the subsequent phases of COVID-19 that are gradually unfolding and are likely to last the next 18 months or more. Financial service providers can play a vital role in strengthening the resilience of young people in the face of these challenges by offering the types of appropriate savings services and products described in this article. It may sound counter-intuitive, but the COVID-19 crisis might be the right moment to ramp up innovation and outreach around savings services.

By: Mahlet Alemayehu

This first appeared in the Next Billion article https://bit.ly/33AJbT8