How the approach of COVID-19 has affected low-income households in central Bangladesh.

Liaqat (not his real name) is a newspaper vendor and a volunteer ‘diarist’ in the Hrishipara Daily Financial Diaries project. We have been tracking all his money transactions on a daily basis since October 2015.

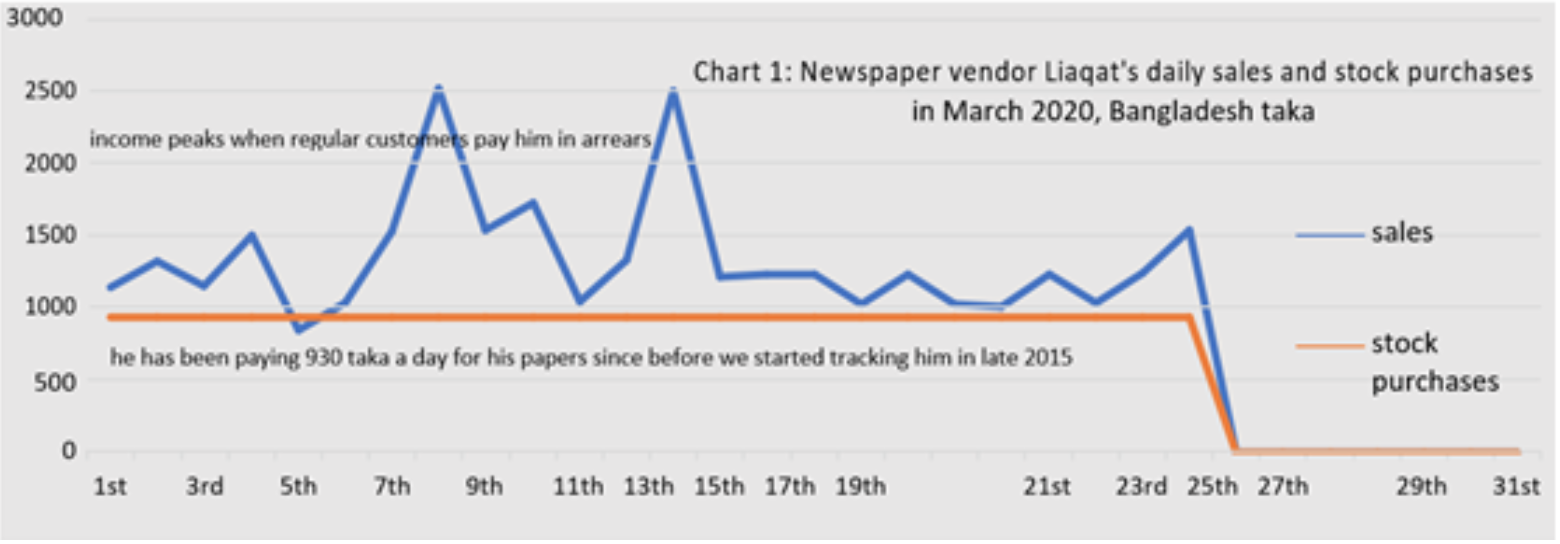

Selling papers is his only source of income. Early each morning, seven days a week, he buys papers for 930 takas (about $26 at the PPP exchange rate). He sells about half of them, for cash, on the street, and delivers the rest to regular customers who pay him in arrears. Averaged out over the years, his sales have exceeded his stock purchases by just over 40%, giving him a net daily income of 380 takas (PPP$ 10.60) for himself, his wife, his three daughters, and his son. As Chart 1 shows, this pattern came to an abrupt end on 25th March 2020.

At the beginning of March, the papers Liaqat sold (all of them Bengali language) were treating the COVID-19 outbreak largely as an overseas story. But on 9th March they reported the first three confirmed cases in the country and began to editorialize about Bangladesh’s weak health system and the low rate of testing for the virus. On 16th the government closed the country’s leading University. More cases were confirmed and on the 18th came the first death. On the 23rd there were reports of a ‘cluster’ of cases in a village about 10km from our area and later that day the government announced that a nationwide ‘lockdown’ of all offices and shops would start on the 26th. By the time 26th arrived, Liaqat had relinquished his livelihood: he could have got papers to sell, but there were too few people on the streets to sell them to – and he was very frightened of catching the virus.

Not just newspaper vendors, not just business income

The 60 diarists that we track enjoy various kinds of money inflow. Some, like Liaqat, have business income, where costs have to be subtracted from gross sales to arrive at net income: they include several shopkeepers. Others earn daily income through casual labor or self-employment like driving rickshaws or ferryboats. Others have regular income – office cleaners and drivers and factory workers get a weekly or monthly wage, for example. Then there are remittances sent from overseas, gifts from family and friends, and welfare payments.

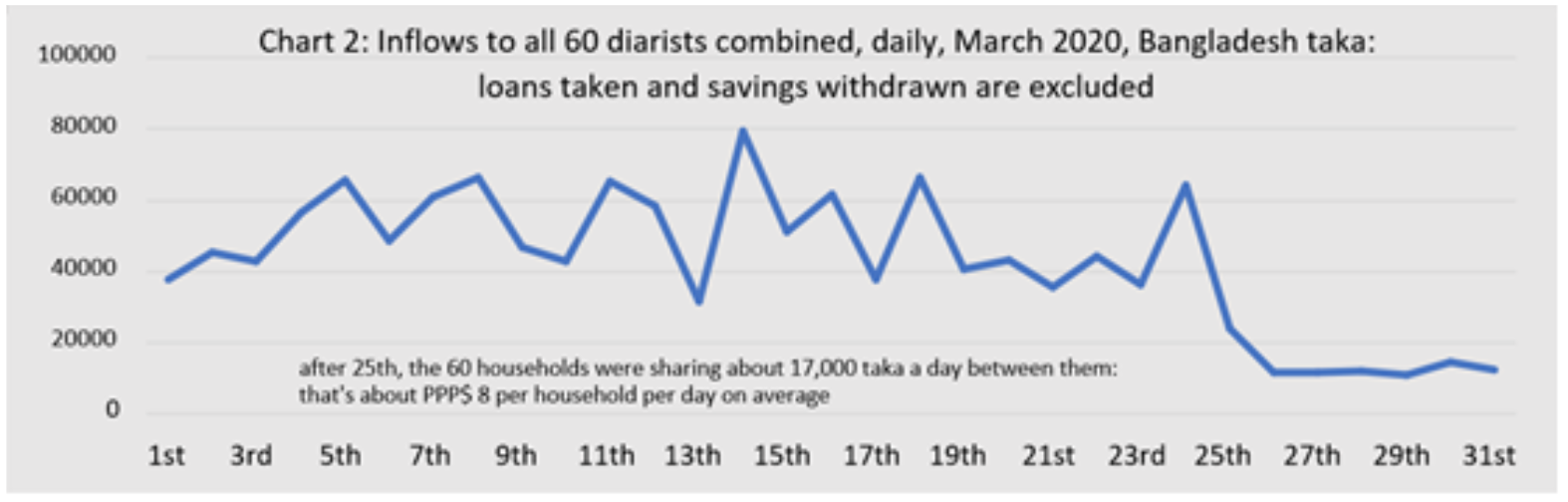

In Chart 2, below, we show the aggregated daily totals for these inflows, for all 60 diarists combined. Notice that we have omitted financial inflows – the loans they take and the savings they withdraw: we will deal with them separately.

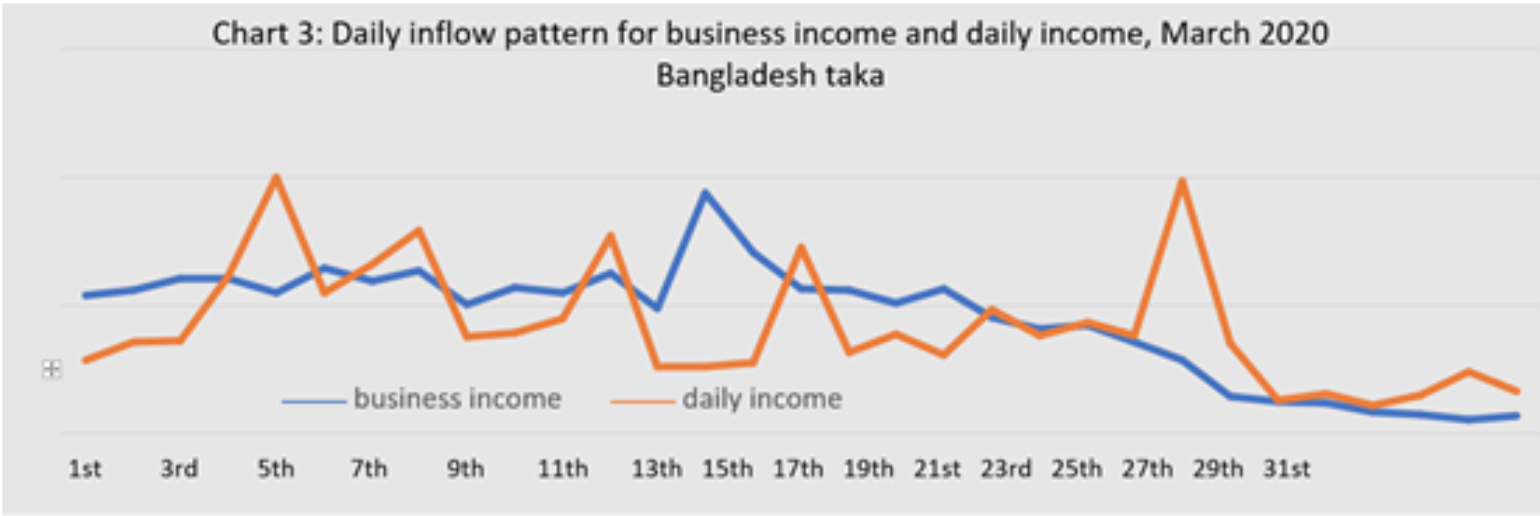

Evidently, income suffered a general collapse around 25th March. Of the various income streams, regular income shows a less precipitous decline, because pay days don’t necessarily come at the month’s end. In Chart 3 we show how business income declined from its usual relatively steady state, as shops and restaurants closed. Daily income, which usually shows many ups-and-downs as our diarists succeed or fail to get daily work, or get paid late, flattened as jobs dried up.

Remittances from overseas – enjoyed by a dozen or so of our diarists – have not filled the gap. We cannot say that they have declined since they tend to arrive at irregular intervals, but they have notably not picked up at the month’s end. Diarists report that many of their family members overseas have lost their jobs or not been able to work: some are themselves in acute difficulties.

Welfare cash payments, of low volume at the best of times, have yet to respond to the emergency. On 28th March two diarists received baskets of foodstuffs from a government COVID-19-related relief program and by the end of the month, another two diarists received similar packages (one via the main opposition political party).

Loans and Savings

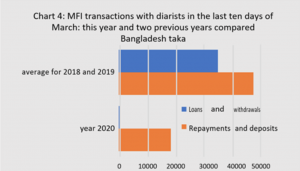

Most of our diarists are clients of microfinance providers (MFIs) and for many of them, MFIs are where they keep most of their cash savings. But many MFIs have shut down in conformity with the government lockdown. We were told by the Manager of the local branch of Grameen Bank, a leading MFI with more accounts among our diarists than any other, that his head office instructed him to cease all transactions – including the release of savings. We illustrate the effect of this in Chart 4 where we compare the last ten days of March 2020 with the same period in the two previous years. MFI loans and savings withdrawals – essential resources when people are in difficulty – have stopped. The Co-operatives and the informal devices (informal loans, money-guards, and local savings-and-loan clubs) also lent less and released fewer savings in the last ten days of March 2020, but – perhaps because they didn’t fully close down – they took in more loan repayments and more savings than the MFIs did. The leading Co-operative tells us it will find a way to release savings to clients who need them during the crisis, but observes that demand has so far been low. Most diarist households hold some cash reserves at home and it may be that they are using them before calling on their savings.

Spending

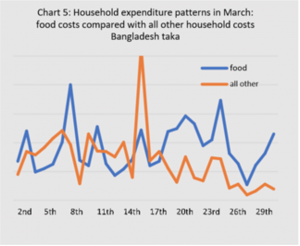

Immediately after the declaration of the lockdown, we noticed a fall in all spending. Food spending fell to the lowest we have ever seen on the 28th. However, in the last three days of the month food spending picked up a little (shops are mostly closed but some market stalls are still running). Other household expenditures (healthcare, education, transport, utilities, household supplies, snacks and tobacco, and so on) are still at historic lows, suggesting that diarists may be prioritizing food buying over other household needs. Chart 5 illustrates this (the spike in expenditure on 16th was the payment for a gall-bladder operation).

Overview and Priorities

At the time of writing, on the evening of March 31st, confirmed infections in Bangladesh reached 54 and there had been six deaths. The government extended the term of the lockdown to April 11th. As yet, there are no cases of COVID-19 recorded or suspected in the communities where our diarists live. Nevertheless, local people are very aware of the threat. Many, like Liaqat, are afraid to venture out on the streets. If they do, there are police and military patrols to shoo them back home.

Anxiety prevails, as shown in the end-March version of the monthly survey we take of our diarists’ thoughts about the month just past, and their hopes for the month to come. The fear, overwhelmingly, is of loss of income.

A rickshaw driver: “March was bad regarding income as well as mental anxiety, due to corona”.

A widow: “March was bad because my daughter, who is overseas, is now unemployed. I am in acute anxiety due to corona”.

A woman who runs a small shop: “March was bad because neither my son nor his wife can go to work and we’re all very anxious, all because of corona”.

Much of what needs to be done by policymakers is already understood. This blog testifies to, rather than reveals, those needs. What is described here suggests that from the diarists’ point of view the top priorities are relief measures to ensure food and income security and to prevent distress sales of assets. Financial services need to be unlocked, above all to release savings in MFI accounts. And the high level of anxiety means people need, somehow, to be reassured.

Stuart Rutherford

March 31st, 2020

All fieldwork for the Hrishipara Daily Diaries Project is now being funded by L-IFT. We gratefully acknowledge their invaluable support.

Read more analysis based on the Hrishipara Diaries:

- Low-income households in Bangladesh give as well as take loans

- Education and Occupations

- How are Digital Financial Services used by poor people in Bangladesh?

- What the poor spend on health care?

- How the poor borrow?

- What do poor households spend their money on?

- Tracking the savings of poor households

- When poor households spend big

- When poor households spend big part 2

- Poverty measurement using data from the Hrishipara daily financial diaries

- Receiving Gifts in Low-Income Households

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.

This article was simultaneously published by Manchester University and MSC.